How The Kyebi Ritual Murder Of 1944 Accelerated The Campaign For Ghana’s Independence

By Ekow Nelson

Photo Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery

The Kyebi Ritual Murder and the protracted legal battle that followed it had more influence on Ghana’s politics than many appreciate. For some inexplicable reason, and rather worrisomely, not much is written about it in Ghana and it is hardly ever discussed – not even in the context of the biography of its key defence protagonist, Dr. J.B. Danquah. There is a deafening silence about his role in the interminable legal wrangle that followed the horrific murder of the Odikro of Apedwa, Nana Akyea Mensah.

Murder at the Omanhene’s Palace

Six months after the death of Nana Sir Ofori Atta I in August 1943, the Odikro of Apedwa disappeared. According to evidence presented at the trial that followed, while Nana Akyea Mensah was on his way to the Palace to perform the traditional custom of Wirempe – the consecration of the stool of the deceased Omanhene with ‘a mixture of soot, eggs, and the blood of a dog and brown sheep’ [Rathbone] – he was attacked in one of the courtyards, given a drink (presumably to drug or poison him), struck on the back and a ceremonial dagger thrust through his cheeks to stop him from screaming.

According to Kofi Ellison, such executions were sudden and quick. The executioners, he wrote, “would have first, stuck a sharp knife through the victim’s cheeks. This act is called “Sɛpɔ,” y’abɔ no Sɛpɔ” or (one is hit with a Sɛpɔ), accomplished two things: It locked his jaws;and prevented him from being able to utter any words.

The latter is very important to prevent the victim from invoking a curse; invoking NTAM (Oath), which would trigger a complete cessation of whatever was intended; or otherwise uttering anything that might bring untold hardship on those doing the act, and/or their families.”

It is not clear why the Odikro, who is also said to have been the illegitimate son of the deceased Omanhene, was specifically targeted for murder. Some say he was killed because there was a quarrel about the use of human blood in the stool blackening ceremony and he was in a minority of one that came out against the practice. And since Wirempe rites were traditionally performed by the Odikro of Apedwa, it became necessary to eliminate him.

Others say that as a confidant of the dead Omanhene he knew far too much about the family’s finances which made him a target for elimination.

Regardless of the true motivations, it is inconceivable that the killers acted alone, or without authority or support. The great lengths the defence team went to obstruct justice and the considerable expense incurred in legal fees both in Ghana and abroad, funded by the royal family, bears testimony to the institutional support the murderers received from the Akyem Abuakwa Establishment.

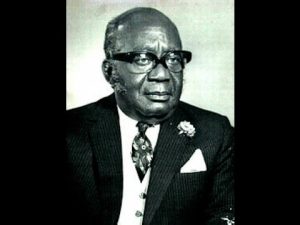

Dr. Danquah rides to rescue the defence

If John Mensah Sarbah was the celebrated nationalist of the Gold Coast at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, and Casely Hayford the dominant one among the Intelligentsia in the early quarter of the 20th century, Dr. Danquah was, without doubt, the leading Gold Coast nationalist of the 1940s. Apart from his half-brother, Nana Sir Ofori Atta I, Omanhene of Akyem Abuakwa, there was no other nationalist of similar stature who wielded as much influence in Accra, Kyebi, Saltpond and London on behalf of the Gold Coast, from the late 1930s to the end of the 1940s.

When Dr. Danquah became the inspiration and mastermind for the defence of the accused in the murder of the Odikro, the impact on the Colonial government – which was determined to prosecute the case – was cataclysmic. Subsequent interventions by high-profile British political figures from Winston Churchill (who argued against executing the murderers), Quintin Hogg (later Lord Chancellor Viscount Hailsham), R.A. Butler (author of the famous British 1944 Education Act), and Hartley Shawcross (the post-war Labour Attorney General) in the case, and attempts to remove Governor Alan Burns with whom Dr. Danquah had previously formed a close partnership, is testament to the reverberations it caused.

Dr. Danquah was so unassailable (or so he thought) that he was in no doubt that he would prevail at the trial. He assembled a crack legal team including, Nii Amaah Ollenu (later to become Speaker of Parliament in Ghana’s Second Republic), Edward Akufo-Addo (father of the current President, Nana Addo Danquah Akufo Addo) and Sarkodee-Addo (both of whom went on to be Chief Justices of the Supreme Court of Ghana).

With the best legal minds assembled, and relationships with the law and the powers of the land firmly in place, it was inconceivable to many of them, especially Dr. Danquah, that he could lose this case. So, when a jury of six Gold Coast natives and one European unanimously returned the verdict of guilty at the trial in Accra in November 1944, it came as a shock to the local intellectual establishment.

The people clearly expected differently; according to the British Spectator magazine, ‘when the jury gave a verdict of “Guilty” a great roar went up from the crowd of over a thousand packed into the court’

A plea for exceptionalism for our native customs, it was thought, would weaken the resolve of the Governor and prosecuting authorities – and it almost did work, judging by the numerous parliamentary interventions made in London. The defence assumed that insinuating that foreigners were interfering in local customs would elicit sympathy from ordinary people. But they were wrong.

For the ordinary people of Apedwa and even much of Akyem Abuakwa, however, this was an open and shut case of murder and the perpetrators had to pay. As Burns put it, ‘the people of Apedwa, -under great provocation, were persuaded to take no revenge for the murder of their Odikro, but I am convinced that if some at least of the murderers had not been executed they would have taken a bloody revenge on those they held responsible’.

Multiplicity of Privy Council Appeals

What followed was a multiplicity of appeals and delay tactics deliberately designed by lawyers of the accused to frustrate, even undermine, the rule of law and the Governor by preventing him from carrying out the sentences as required by law. Right after the trial, the defence led by Dr. Danquah lodged an appeal with the West African Court of Appeal which was dismissed the following February 1945.

After this, the stage moved to London for a heightened campaign of appeals and intensive lobbying. For three years the legal wrangle dragged on from one appeal to another.

Here is a flavour of the defence’s elaborate and high-intensity appeals designed to frustrate justice:

The first Privy Council appeal lodged in November 1945 was dismissed; an appeal to the Supreme Court followed and that too was rejected; this was followed by an application for special leave to petition the Privy Council against the Supreme Court’s decision which was also quashed; an application for the Attorney General to issue a writ of error was filed but he refused; the Supreme Court was asked to compel the Attorney General to issue the writ of error and that was thrown out; the decision of the Supreme Court was appealed to the Privy Council in July 1946 and once again it was dismissed; the defence then brought civil proceedings against the Attorney General which was roundly rejected by the Supreme Court; they appealed this decision to the West African Appeal Court and they were rebuffed; and, as had become routine, another application for leave to appeal to the Privy Council was lodged again.

The rapid succession of exhausting appeals and counter-appeals were as unprecedented as unexpected, designed in the hope, that the Colonial government could be prevailed upon to commute the sentences.

Lobbying and campaigns to smear the Judge and the Governor

At the same time, an elaborate lobbying campaign among sympathetic British parliamentarians was launched. Supporters of the defence lost no opportunity to exploit every loophole or parliamentary quirk or procedure to raise the issue to embarrass the Colonial Government. The spectre of a ‘white’ Colonial Governor putting black Africans to death, smacked of the bad of old days when ‘whitey’ held the whip over the black man – that was the narrative that the defence peddled so effectively, even Winston Churchill joined the chorus of appeals even when he did not know the facts of the case.

A campaign to stop the Governor from carrying out the executions of the convicted murderers began in earnest. A telegram detailing the defence’s objections was sent to the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Among the grievances were:

(i) that the six native jurors were from a different tribe to the accused; even though the defence did not object to them when they were empanelled; and

(ii) ‘that the Trial Judge was a Turk and a Mohammedan’; which Governor Alan Burns described as ‘a disgusting example of racial prejudice and religious intolerance for which I have utter contempt’

It fell to the Economist Newspaper to call order on the campaign of misinformation. On 8th March 1947, it chided members of parliament thus:

‘In matters of justice it is usually the best course to trust the juries, the judges and the executive authorities who are on the spot. If Members of Parliament are not prepared to do that, they should at least inform themselves of the facts.’

Still some members contemplated drawing in His Majesty to grant pardon and thereby overrule the Governor and the jury.

The pressure on the Governor was unrelenting but he said to himself that if he gave way ‘the people of the Gold Coast would feel, with some justification, that one in whom they had trusted had betrayed them’.

When the pressure became intolerable, the honourable course of action left for Burns was to offer to resign his post as Governor since he could not in good conscience unilaterally commute the sentences of murderers who had been found guilty by a jury of six Africans and one European. The Secretary of State rejected his offer of resignation and for the first time Parliament convened to hear the full facts of the case and at the end, the government reaffirmed its full support for the Governor.

What happened next showed the depth of support the Governor’s unyielding position had in the Gold Coast. In an open letter to the Governor published on 8th March 1947, The Ashanti Pioneer, assured him of support of the Gold Coast public whom it said, were solidly behind his actions. ‘However much the Parliamentary wolves growl against you, our feelings towards you will never change’, the paper assured the Governor.

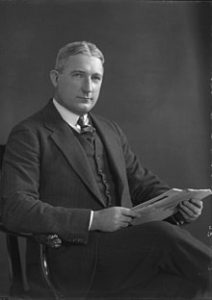

Photo Courtesy: Wikipedia

The people of Akyem Abuakwa, enraged by the antics of Dr Danquah and his defence team, sent strongly worded telegrams of protest to the Colonial Secretary, Creech Jones. The Akyem Abuakwa Council urged him not to yield to the demands of the defence. Commuting the sentences of the murderers of Akyea Mensah would be a ‘perversion of justice and would have untold ramifications on the Gold Coast’ they argued. The murderers should be treated as they would in Britain. And in a chilling warning said, if ‘British justice fails to atone for the innocent blood of Akyea Mensah, surely we can avenge this death of our chief’.

There was strong support too from the Chiefs; 62 of the 63 in the Joint Provincial Council urged the Governor not to resign; 17 of the 18 members of the Gold Coast Legislative Council backed a resolution of support for the Governor; crucially only Dr. J.B. Danquah, the defence mastermind and relative of the convicted murderers refused to support the Governor.

Ultimate repudiation of a wealthy defence’s attempt to get away with murder

Buoyed by the show of support, the Governor took on his critics in a moving speech to the Legislative Council. To those who said the trial was unfair, he responded thus: ‘these murderers were found guilty by a jury of whom all but one were Africans, and that the case has three times been up to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which has, on each occasion, refused permission to appeal. I have been advised by my legal advisers, and the Secretary of State has been, advised by his legal advisers, that in this case there has been no miscarriage of justice.’

On the use of capital punishment, he said: ‘I am myself no enthusiast for capital punishment, but, so long as it is the penalty prescribed by law for the crime of murder, that law must be carried out, and it should, I am convinced, be applied equally to rich and poor alike’

Then in a scathing passage, he excoriated the defence team for thinking they could get away with murder, literally, because of their wealth and standing in society. ‘Because they were wealthy, and of an influential family, they were able by means of a subtle propaganda to enlist the sympathy of people in England as poorer and less influential men could not have done’ Burns said.

Reaffirming the moral covenant of his role as Governor and his juridical responsibilities, he said: ‘I have firmly refused to be a party to what I believe to be wrong, and to show mercy to rich men which I would not have shown to the poor. It is my duty to administer the Government of this Colony without fear or favour, that is, without favour to the rich and influential, and without fear of the consequences to myself. I am convinced that the action I have taken in this matter was correct’

He concluded correctly, that if he had yielded to the demands of Dr. Danquah and the defence, a precedent would have been established for British politicians in faraway London, to overturn the verdicts of the courts in the colonies. Is that what Dr. Danquah wanted? Or did it not matter because his relatives were the ones in the dock for murder?

Still, it did not end there; there was one further last Privy Council hearing in July 1947 (take a second look at the date). After rejecting the appeal, Lord Thankerton made this unprecedented scathing attack on the defence:

‘Their Lordships viewed with grave concern and disapproval, the unusual procedure adopted in this case in the multiplication of applications to the Board. Their Lordships found it difficult to avoid the conclusion that the course was either adopted deliberately which would constitute an abuse of the due administration of justice or arose from an inexcusable ignorance or disregard of the laws, procedural or otherwise, involved’ – The Times Law Report of I7 July 1947.

Dr. Danquah seeks revenge

In Richard Rathbone’s book on the murder – A Murder in the Colonial Gold Coast: Law and Politics in the 1940s – the next sentence after quoting Lord Thankerton is this: ‘A month later Dr. Danquah, one of his younger brothers and another of the defence counsel had, with seven others, launched the United Gold Coast Convention which most analysts regard as the first full-blown nationalist party in modern Ghanaian history’.

The United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) was formed on August 4th, 1947 just a little less than one month after the Privy Council shut the door on further appeals. Indeed, it did not escape Rathbone’s notice too that ‘three of the ten men who founded [the UGCC], a month after the execution of three of the accused [in the Ritual Murder], included Danquah, his half-brother William Ofori-Atta and E. A. Akuffo-Addo, one of the defence lawyers’.

My auntie whose family had close relationships with Dr. Danquah and whose father edited The Ashanti Pioneer, once told me that after the case, Dr. Danquah visited Saltpond. And at a meeting or rally which she attended, he said this, in Fante, in reaction to the execution of the those found guilty of the Odikro’s murder: “Sɛ obronyi bo ku hɛn a, bronyi bɔ kɔ ni krom”, that is, ‘if the white man is going to kill us; we will send the white man back home’.

Whatever plans may have been made before, it is not surprising that the Governor’s determination to pursue the killers of Akyea Mensah, had a huge influence on Dr. Danquah’s political posture and attitude towards the Colonial government and it was a significant motivating factor for setting up the UGCC. As Dr. Nkrumah observed in his Autobiography, after the final judgment in the case, Dr. Danquah ‘withdrew his support from the Burns Constitution and started agitating for a new one’.

Decline and Fall

What happened after the launch of the UGCC and the invitation of Nkrumah to be General Secretary, however, changed everything and in a remarkable twist of irony, marked the end of Dr. Danquah’s dominance in Gold Coast Affairs.

It began with the elections of 1951 which the UGCC lost to the CPP (founded by Dr. Nkrumah), including in Dr. Danquah’ ancestral home of Akyem Abuakwa. He just about secured a seat in the new Legislative Assembly because of an electoral college system designed for towns and cities outside the main municipalities of Accra, Cape Coast and Sekondi.

As with the Akyea Mensah case, Dr. Danquah did not take losing well. He bragged in a debate in 1952 in the first All-African Legislative Assembly that he was a well-known Constitution wrecker; I have already destroyed two and will happily wreck a third, he said of the 1951 Constitution. But after 1954 when he lost his seat, it was clear that his influence was at an end.

The prosecution of the murderers of the Odikro may have motivated him to move against his British collaborators, but it revealed the depth of antipathy that many of his own developed for him. As Rathbone says, ‘Danquah himself was not universally loved, as events in the later I940s and throughout the I950s were to show more clearly than the generally rather uncritical analysis which has followed his sad death’.

Disgrace and collective embarrassment

The source of much of that discontent was the well of his support base – his home. The Odikro’s unexplained disappearance for five months, and rumours that he had been killed while visiting the Kyebi Palace to partake in the funeral rites for the dead Chief, touched a raw nerve and had a sobering and sorrowful effect on subjects whose loyalties had by now been stretched too far. The loss of a great and distinguished Omanhene, Nana Sir Ofori Atta I, was tragic enough; but losing an admired Odikro at the hands of the very Palace where he had gone to mourn was embarrassing and tragic.

Most people wanted the issue resolved quickly to allow the community to pick up the pieces and get on with their lives. The sight of luminaries from the Akyem Abuakwa Royal Family, including the Ofori-Attas, Amoako-Attas etc, trudging off to court to offer testimony, alongside sons of the dead Omanhene in the dock, charged with murder, was most painful to witness. This was a great tragedy that struck at the very core of the symbolic power of the Akyem people. It was humiliating, and everyone wanted it to end.

But for three years, Dr. Danquah and his defence team dragged the case through the courts attracting high profile publicity in the local and foreign press, many of whom were all too keen to sensationalise the nativist practice at the centre of the tragedy which has no place in the modern world.

When Dr. Danquah decided to form a political party, possibly out of pique at the verdict, little did he appreciate the toll the entire saga had taken on his people. These were the very people who had hereto lauded him, and yet they denied him access to the exalted position of power they had prepared him for. He lost his people, his friends in the British Establishment, his Burns Constitution and even lost his UGCC.

Conspiracy of ‘deafening’ silence

No surprise then, that Nkrumah called the Kyebi Ritual Murder a watershed in the historical development of our independence. Sadly, we don’t teach it; write about it; discuss it or even try to understand it despite its far-reaching impact.

For example, four of the murderers were given life imprisonment but no one knows what happened to them. There is a strong suspicion they were released quietly after the 1966 coup when the current President’s father was Chief Justice. Others say President Nkrumah released them as an act of clemency at independence. Why were they released? Had they served their minimum terms? We do not have answers to these questions. The conspiracy of silence on this issue by our historians and journalists is greatly lamentable, even unpardonable.

Scholarly works on this under-appreciated cataclysmic, so-called ‘juju killings’, have been left to foreign scholars like Richard Rathbone and Bonny Ibhawoh. Perhaps it is too raw and painful? Perhaps too embarrassing, particularly if it means highlighting the role Dr. Danquah played in all of it, given his near-sainthood since his death, and thereby undermine the narrative for his supporters and detractors alike

In our quietest moments we might want to reflect, at a human level, upon the parallels between Dr. Danquah’s eventual demise in detention and his public posture over the murder of Nana Akyea Mensah along with his starring his role in dragging the case interminably through the courts, without a moment’s thought on the impact on the family of the Odikro and the people of Apedwa.

Rio de Janeiro

May 17th, 2018

Sources:

- H.A. Nuamah, Murder in the palace at Kibi : an account of the Kibi ritual murder case, 1985.

- (UK) National Archives, Trial for alleged murder of Odikro of Apedwa, CO 96/783/2, 1946

- Richard Rathbone, A Murder in the Colonial Gold Coast, 1993

- Bonny, Ibhawoh, Imperial Justice: Africans in Empire’s Court, 2013

- Sir Alan Burns, Colonial Civil Servant, 1949

- UK Spectator Magazine, 23 MARCH 1945

- Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah, 1956

- Geoffrey Bing, Reap the Whirlwind: An Account of Nkrumah’s Ghana from 1950 to 1966, 1968;

- Dennis Austin, Politics in Ghana 1946-1960, 1970

- Creech Jones, 1929-1964 Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford University

- Richard Rathbone (Ed), British Documents on the End of Empire: Ghana, 1992

- Ralph Uwechue (Ed), Makers of Modern Africa: Profiles in History, 1991

This piece was originally published on ekownelson.wordpress.com